|

December 20-28.

It was time to head north toward the Honduran border, and learn about life in the campo along the

way.

During this period, and perhaps sometimes in subgroups, we visited Esteli; Condega; Pueblo Nuevo;

Palacaguina; a government project named after the Nicarguan patriot—and assuredly poet as

well—Rigoberto Lopez Pérez, and the coffee cooperative El Chaguiton.

We left Managua at noon on December 20th for a big welcome in Esteli at 3 p.m. On the 21st, I played foreign

correspondent, with the help of Theresa from Canada kindly acting as translator. (Theresa was at least

tri-lingual: French, Spanish, English.)

We interviewed a hotel manager,

Ricardo. (Not his real name. Not knowing attribution protocols, I will opt for anonymity for

the manager here.)

Ricardo was not a great fan of the Sandinistas, but he told us that they were practical, and not

committed to anything like the "communist model" that Washington accused them of.

Ricardo said that many of the nation's buses were being sold to private entrepreneurs, and that the

Hotel Descapa

was being built by the state but would be turned over to the company that ran the Intercontinental. He said

that the state provided scholarships to the tourism school, so Nicaragua could tap into the increasing market

for south-of-the-border R&R.

Ricardo also said that, at least in Esteli, there was no Eastern Bloc presence. His final

comment was that the U.S. was "in error" with its contra program.

We also visited Condega and Palacaguina on the 21st. With the people of Palacaguina we sang Cristo de Palacaguina,

one of my very favorite songs. I have it on Sabiá's famous Green Tape, the first of

their several popular recordings of Nuevo Canción. The people of Palacaguina then sang the Sandinista

anthem, with great pride as always.

Our next stop was the Rigoberto Lopez Pérez project, made up of about three hundred

very militant workers and soldiers. My notes don't show what the project was about, so I welcome any

information that a visitor to this site might be able to supply.

My notes show the 22nd as a day of rest and washing, but it also seems that I went along on a rather bumpy

ride in the back of a flatbed truck, accompanied by about 15 soldiers, to Pueblo Nuevo.

Here, in small, personal meetings with the Mothers of the Heroes and Martyrs, the FSLN representatives

expressed their support,

and their understanding of how difficult it was for these women to celebrate Christmas without their sons and

daughters. These sentiments were expressed with a great measure of pride, dignity, and gentleness.

Later, the mothers said to us: "We may suffer, but we know how to celebrate—the mothers invite you to

dance." And, so we did. There was also spontaneous singing by all in the park as we waited for the trucks to

take us back, on the same bumpy road, to Esteli. Some day of rest!

|

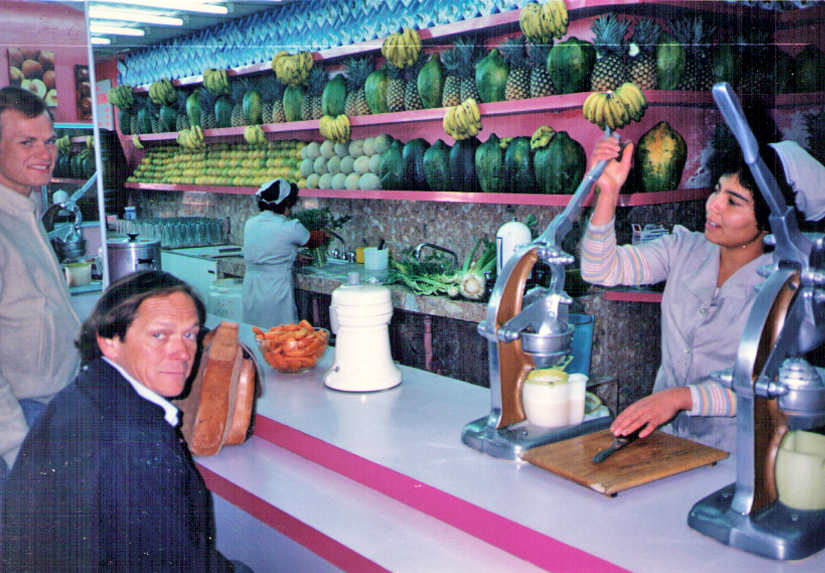

December, 2010. This, and the next two photos are of Phil Otis, who was an important member of the documentary film team. Phil died recently, and Kent Strumpel, who took these pictures, has given me permission to post them in his memory. I have placed them at the front of this page because it seems to be about the right time frame.

December, 2010. This, and the next two photos are of Phil Otis, who was an important member of the documentary film team. Phil died recently, and Kent Strumpel, who took these pictures, has given me permission to post them in his memory. I have placed them at the front of this page because it seems to be about the right time frame. Here Gary Meyer, another film crew member, and Phil sit at a restaurant, probably Mexico City.

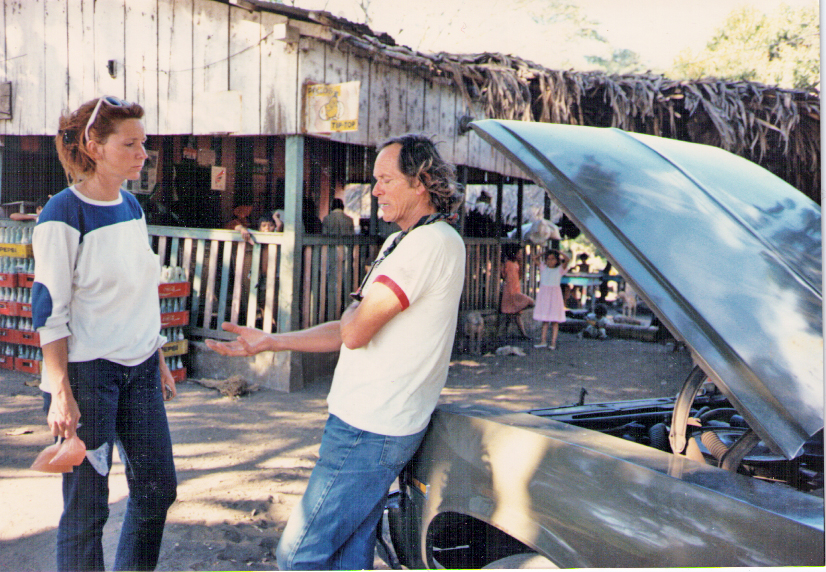

Here Gary Meyer, another film crew member, and Phil sit at a restaurant, probably Mexico City. The film crew's taxi broke down on the way to the Nicaraguan port town of Potosí, on the gulf between Nicaragua and El Salvador. They wanted to get footage of the Salvadoran peace activists who still hoped to meet us, even though the Salvadoran government said that we could not enter. The idea was to cross the gulf in boats, and somehow rely on international pressure to allow the filming to proceed. The plan was not realized, and I am sure that the crew would not be here today had they succeeded in landing on El Salvador's shore.

The film crew's taxi broke down on the way to the Nicaraguan port town of Potosí, on the gulf between Nicaragua and El Salvador. They wanted to get footage of the Salvadoran peace activists who still hoped to meet us, even though the Salvadoran government said that we could not enter. The idea was to cross the gulf in boats, and somehow rely on international pressure to allow the filming to proceed. The plan was not realized, and I am sure that the crew would not be here today had they succeeded in landing on El Salvador's shore. Monday, December 23.

Monday, December 23. My notes say that we were supposed to pick coffee while at El Chaguiton, but that most all the pickers were

on Christmas vacation so there was no one to teach us. Here, those who stayed behind line up to receive their

lunches for a day picking the coffee.

My notes say that we were supposed to pick coffee while at El Chaguiton, but that most all the pickers were

on Christmas vacation so there was no one to teach us. Here, those who stayed behind line up to receive their

lunches for a day picking the coffee.

A coffee plant with berries ready for harvest. Very pretty.

A coffee plant with berries ready for harvest. Very pretty. Here California farm worker Francisco discusses guitar theory with some of El Chaguiton's musicians.

Guitars were everywhere in Nicaragua, and on la marcha, too.

Here California farm worker Francisco discusses guitar theory with some of El Chaguiton's musicians.

Guitars were everywhere in Nicaragua, and on la marcha, too.

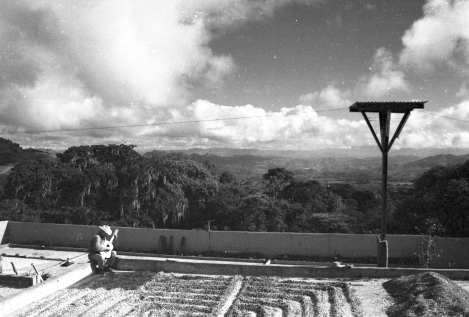

A wider view of the same scene. If I recall correctly,

the first step in processing coffee after picking is to soak and wash the beans. Then they are spread in rows

on the concrete to dry. I think the hulls, which have been somewhat separated from the bean by soaking,

give the rows their dark color here.

A wider view of the same scene. If I recall correctly,

the first step in processing coffee after picking is to soak and wash the beans. Then they are spread in rows

on the concrete to dry. I think the hulls, which have been somewhat separated from the bean by soaking,

give the rows their dark color here.  Here, if I'm not mistaken, the hulls have been stripped from the beans, which are regularly turned over until

they are ready for roasting.

Here, if I'm not mistaken, the hulls have been stripped from the beans, which are regularly turned over until

they are ready for roasting.  Francisco serenades the coffee.

Francisco serenades the coffee.

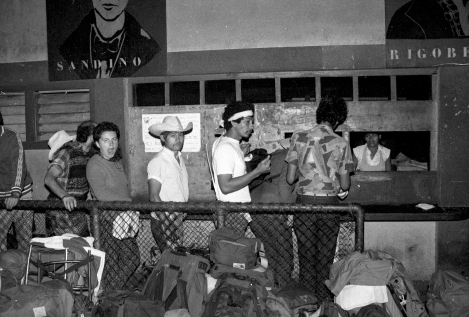

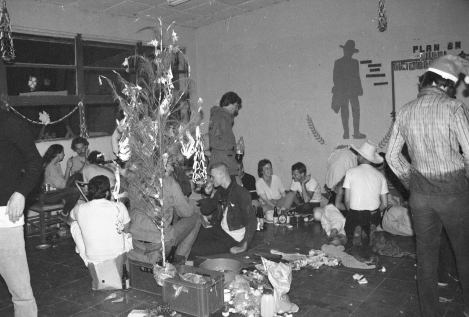

I'm not really sure where we are here. The posters indicate that we might be at the Rigoberto Lopez

Pérez enterprise.

I'm not really sure where we are here. The posters indicate that we might be at the Rigoberto Lopez

Pérez enterprise.

Soldiers leave for a day on patrol. There was no action in the neighborhood while we were at El Chaguiton,

possibly because of our presence there.

Soldiers leave for a day on patrol. There was no action in the neighborhood while we were at El Chaguiton,

possibly because of our presence there. I'm not sure that this photo belongs here. It is night, past the time of the dancing and singing I mention above.

In any case, here Marshall and a Nicaraguan woman enjoy each other's company on a dance floor somewhere.

I'm not sure that this photo belongs here. It is night, past the time of the dancing and singing I mention above.

In any case, here Marshall and a Nicaraguan woman enjoy each other's company on a dance floor somewhere.

This could be Pueblo Nuevo—I don't know. Here Marshall assists one of our Spanish marchistas (I think) in

entertaining the townspeople with some magic tricks.

This could be Pueblo Nuevo—I don't know. Here Marshall assists one of our Spanish marchistas (I think) in

entertaining the townspeople with some magic tricks. Tuesday, Christmas Eve, 1985.

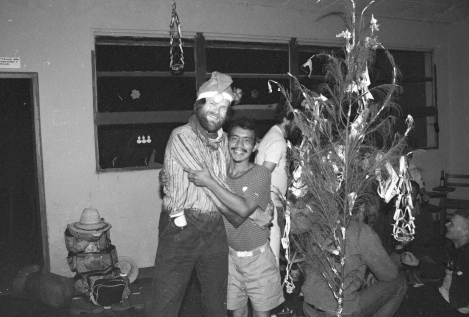

Tuesday, Christmas Eve, 1985. An expression of genuine solidarity and friendship transcending all culture and

language.

An expression of genuine solidarity and friendship transcending all culture and

language.

Thanks to Jim Staal for identifying Martin Breum, Hanne Seln?s, and Kim Hundevadt with the beard. Sonja Iskov

reclines to Kim's left. The man in the glasses on the right is unidentified.

Thanks to Jim Staal for identifying Martin Breum, Hanne Seln?s, and Kim Hundevadt with the beard. Sonja Iskov

reclines to Kim's left. The man in the glasses on the right is unidentified.

Thursday, December 26.

Thursday, December 26. I snapped this picture as the cameras of the documentary crew were also rolling. (Viva La Paz)

I snapped this picture as the cameras of the documentary crew were also rolling. (Viva La Paz) Friday, December 27.

Friday, December 27. Setting up camp. Jerry from Canada is probably checking for scorpions.

Setting up camp. Jerry from Canada is probably checking for scorpions.

Saturday, December 28.

Saturday, December 28. Our unexpected home for the next 6 days—Escuela Olman Flores E. Sonis (Somis?),serving the small

village of La Playa. The odds were against it, but we had hoped that we would be in Honduras this evening,

meeting with our Honduran support

group and learning about the human rights situation there. Que lastima—it didn't happen.

Our unexpected home for the next 6 days—Escuela Olman Flores E. Sonis (Somis?),serving the small

village of La Playa. The odds were against it, but we had hoped that we would be in Honduras this evening,

meeting with our Honduran support

group and learning about the human rights situation there. Que lastima—it didn't happen.