|

The Salvadoran committee was comprised of union members, teachers, progressive mainstream religious, mothers

of the disappeared, telephone workers, non-governmental human rights activists, and members of Christian

base communities. (These base communities were the outgrowth of the liberation theology originating

at the Vatican II council in 1962, convened by the progressive pope John XXIII. Liberation theology was anathema to

to Washington, and after John died shortly after Vatican II, it was anathema to his successor, John

Paul II. Base community activist immediately became the targets of right-wing death squads.)

It had been decided earlier that the internationalists would travel incognito with the Salvadoran marchers.

Upon arrival in San Salvador on January 2nd, they were met by a Salvadoran priest, and whisked away to

a church. (I assume that the internationalists arrived at El Salvador's International Airport, and were taken to

the capital city, San Salvador, about 20 crow-flight miles to the northwest.)

At the church a meeting was held to decide whether they

should be there at all. Someone said that the international marchers were causing problems for the internal

march, but my notes give no details—only a separate comment that there were three Salvadoran madres groups

that didn't coordinate well even with their own compatriots.

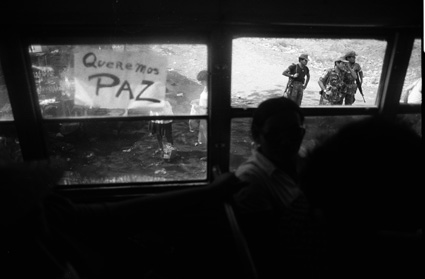

The march began the next morning, January 3rd, with San Francisco Gotera as the first goal on the

way to the liberated zone—where the guerrillas were in control. Some 500 people boarded

13 buses, and there were two cars for journalists. The military set up checkpoints, and prevented the marchers

from getting very far into the countryside. At sundown, the march was ordered to return to the previous checkpoint, where they were ordered either to a

third checkpooint, or back to the one whence they had just come. In any case, the spent an anxious night

on the highway and in a coffee field.

The next morning about 400 of the original marchers began again toward San Francisco. The military had

told the marchers that they had to travel during daylight, but now did not allow them to continue.

They were stopped every 10 kilometers and ordered out of the buses. Their photo ids were checked, and

military cars and helicopters did their best to intimidate them. Soldiers found sheets of peace and

justice songs and deemed them subversive. The marchers were held on the buses without food or water.

That day, a soldier singled out Salvadoran marcher Brigido Sanchez, 46, and accused him of

being a guerrilla. The head of the army arrived and "hugged the prisoner warmly, saying 'don't worry,

you're just going with us.'" The marchers called for the International Red Cross, without success. All efforts to

prevent Sanchez's arrest were in vain. The marchers returned to San Salvador that night, and slept in

the buses in a park.

The next morning, January 5th, the marchers decided to occupy the Basilica. Archbishop Rivera y Damas

opposed this plan, but gave the march permission to sleep in the basement of the cathedral until January 8th.

Torril sent a note to the marchers in Nicaragua asking for

many more of us to come to El Salvador, but I don't recall that happening.

My notes indicate that on January 7, after two nights in the cathedral, the marchers—now "only" 300

strong—again tried to get

into the campo. They were again harrassed at checkpoints and prevented from reaching their goals. They

returned to San Salvador to spend their last night at the cathedral. The

Salvadoran mothers told hideous stories of the torture and murders of their sons and husbands. There was

no one on the Salvadoran march who had not lost a loved one to the repression. The

internationalists were deeply impressed by the courage and committment to peace shown by our Salvadoran

counterparts.

My chronology effectively ends here; I assume that the marchers left the cathedral on January 8th per

instructions, and I show only a suggestion that the 300 of them then went to the University, where they

probably stayed until the march ended on January 13th. I'll conclude this section with some general notes:

If my interpretation of my 20-year-old notes is correct, there El Salvador had four major instruments

of repression—all paid for with U.S. taxpayer dollars, of course: the army; N.G.—National

Guard; N.P—National Police; and T.P.—Treasury Police. I have a vague sense that the Treasury

Police were the most feared and the most brutal.

On Saturday, January 11, some four to five thousand people demonstrated in favor of la marcha and peace.

We learned on the 18th that Archbishop Rivera y Damas had sent a letter to Salvadoran president Duarte

asking—in vain—

for Brigido Sanchez's release.

The marchers in Nicaragua and Guatemala were asked to call home and urge people to call Washington demanding

that Brigido Sanchez be released unharmed. I called my Unitarian Universalist church office, and my social

activist friend/church member Bonnie for good measure.

Sanchez was visited by two human rights groups: first, the official Salvadoran Human Rights Commission; the

next day by unofficial human rights advocates. Tom, from Minnesota, spoke with U.S. Embassy official David

Becker in San Salvador. (Becker is no relation to me, as far as I know.) Becker told Tom that Sanchez

was all right, and was just awaiting trial. Two hours later Tom heard from Sanchez's lawyer, who said

that Sanchez had been badly beaten and drugged. Sanchez was also reported to having confessed to

killing 37 people.

Let me close this commentary with the entirely plausible suggestions

that the unofficial human rights activists told the truth about Sanchez being

tortured and drugged;

that Sanchez had indeed confessed to killing 37 people—to the official human rights commission,

after he had been beaten and drugged;

and

that embassy official Becker, in a shrewd career move, if not through indifference, simply swallowed

whole the offical story without bothering to check for himself.

|