"No major political tendency in Nicaragua was denied access to the electoral process in 1984.

The only parties that did not appear on the ballot were absent by their own choice, not because

of government exclusion. ...

"Opposition parties received their legal allotments of campaign funds and had regular and substantial access

to radio and television. The legally registered opposition parties were able to hold the vast majority of

their rallies unimpeded by pro-FSLN demonstrators or by other kinds of government interference."

Summary of Findings, THE REPORT OF THE LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION

DELEGATION TO OBSERVE THE NICARAGUAN GENERAL ELECTION OF NOVEMBER 4, 1984

.

*******************

From Sandinista Claims Big Election Victory, by Gordon Mott. New York Times, Nov 6, 1984.

"A member of the [opposition] Popular Social Christian Party, José Lazos said his party

'recognized the percentage of the F.S.L.N. vote.' 'It was an honorable process', he said." [Lazos

also confided to the LASA delegation "We received the vote we expected". LASA report,

ibid., p. 18. — B.B.]

"A team of observers from the Washington Office on Latin

America, a church-sponsored lobbying group, said the electoral

process had been 'meaningful' and had provided a political opening

in Nicaragua.

"The group, in a statement prepared after the voting ended on

Sunday, said the process had been 'well conceived' and had

afforded 'easy access to vote with guarantees of secrecy."

*******************

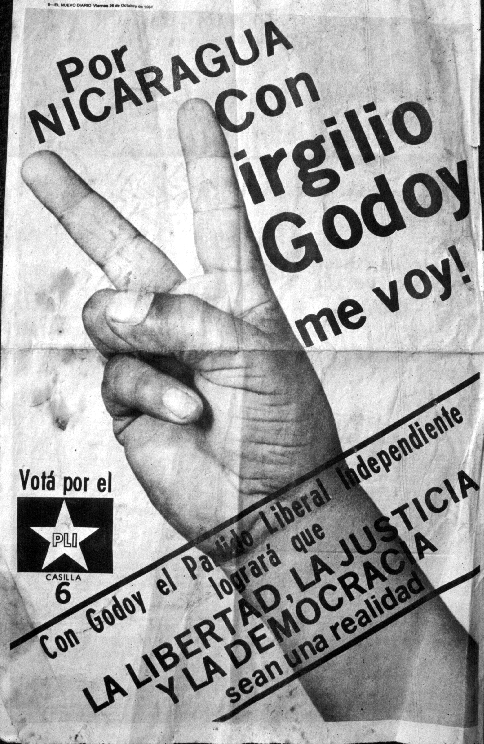

"However, [Virgilio Godoy,the PLI presidential

candidate who dropped out the day after a visit from the U.S. ambassador] went on to compare

favorably Nicaragua's election with presidential elections in El Salvador earlier this year.

'If the US is going to try to be honest in evaluating these elections, it will

be a real problem for the Reagan administration,' Mr. Godoy said.

'If the US administration said that the Guatemalan and Salvadorean elections were valid ones, how can they

condemn elections in Nicaragua, when they have been no worse and probably a lot better than elections in

Salvador and Guatemala.

'The elections here have been much more peaceful. There were no deaths as in the other two countries, where

the opposition were often in fear for their lives.'"

Nicaragua vote seen as better run than Salvador's

By Dennis Volman, Staff writer of The Christian Science Monitor

November 5, 1984, p. 13.

Managua, Nicaragua

*******************

Finally,

"Reviewing the history of the negotiations between the FSLN and the opposition parties since 1981, and

especially during the current election year, Stephen Kinzer, the Managua-based correspondent of The New York

Times, told our delegation

'The FSLN gave in on almost all of the opposition parties' demands concerning how

the electoral process would be run. Their stance seemed to be, "if any clause of the election law causes

serious controversy, we'll modify it." Most of the opposition's complaints about the process had nothing to do

with the mechanics of the elections, but rather were more general criticisms of the political system....

What some of these groups want is a complete change in the political system: to abolish the CDSs

(Sandinista Defense Committees), get the Sandinistas out of the army, prohibit [incumbent] government

officials from running for office, and so forth. In short, they want Nicaraguara to become a parliamentary

democracy first, before they will participate. But this isn't Switzerland!' "

(LASA report, ibid., p. 12.)

|

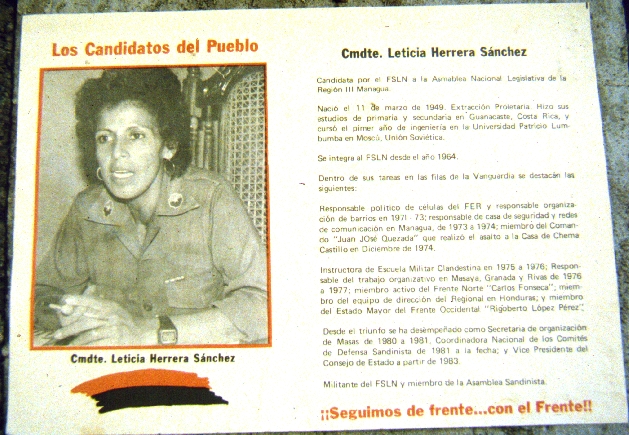

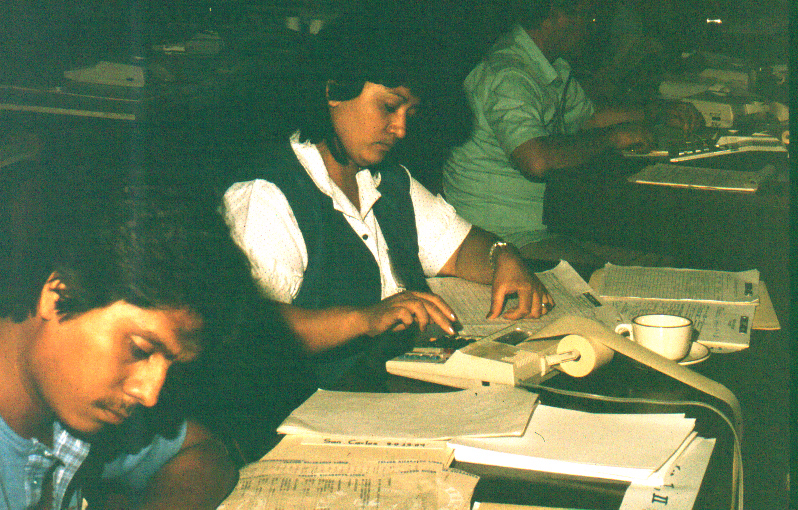

The American CEO's worst nightmare—a Third World citizen organized to oppose the continued domination

of her country's labor, resources, and finances by American capital.

The American CEO's worst nightmare—a Third World citizen organized to oppose the continued domination

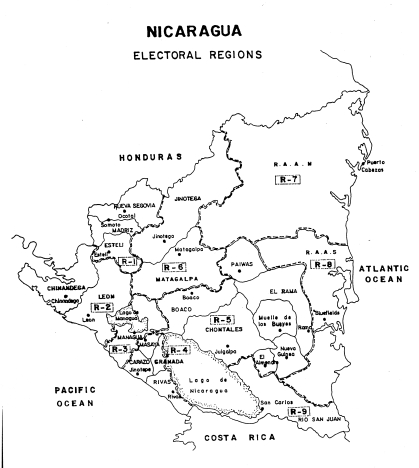

of her country's labor, resources, and finances by American capital.  Nicaragua's political departments, the equivalent of our states. The entire eastern section of Nicaragua,

separated from the west by a mountain range, comprises the largest department, Zelaya. Nicaragua's east coast

was colonized by the British, and the western section by the Spanish. The east coast is the home of several

indigenous peoples, the largest being the Miskitos. The east coast was proseletized primarily by the

Moravian Church, if memory serves. English, rather than Spanish, is the non-native language most commonly

spoken there. Somoza provided training and staging areas on the east coast, and on some of its islands, for the Bay of Pigs

operation against Cuba.

Nicaragua's political departments, the equivalent of our states. The entire eastern section of Nicaragua,

separated from the west by a mountain range, comprises the largest department, Zelaya. Nicaragua's east coast

was colonized by the British, and the western section by the Spanish. The east coast is the home of several

indigenous peoples, the largest being the Miskitos. The east coast was proseletized primarily by the

Moravian Church, if memory serves. English, rather than Spanish, is the non-native language most commonly

spoken there. Somoza provided training and staging areas on the east coast, and on some of its islands, for the Bay of Pigs

operation against Cuba. I do not have a map of the 1984 election's regions, but I assume that they are the same as shown here on the Latin

American Study Association's page for the 1990 election.

I do not have a map of the 1984 election's regions, but I assume that they are the same as shown here on the Latin

American Study Association's page for the 1990 election. The flags of Nicaragua's 7 contending political parties fly outside the Supreme Electoral Council headquarters.

The SEC was the fourth branch of government, and even the bitterest opponents of the Sandinistas did not risk

ridicule by critcizing its integrity or autonomy. By all honest accounts, the SEC conducted the election fairly

and

competently. What irregularities did occur were addressed quickly, and in any case were no more,

and usually far less, egregious than those occuring in other Latin American elections, and even some here in

the U.S. The electoral commissions of Florida and Ohio would do well to adopt SEC methods of conducting an election.

The flags of Nicaragua's 7 contending political parties fly outside the Supreme Electoral Council headquarters.

The SEC was the fourth branch of government, and even the bitterest opponents of the Sandinistas did not risk

ridicule by critcizing its integrity or autonomy. By all honest accounts, the SEC conducted the election fairly

and

competently. What irregularities did occur were addressed quickly, and in any case were no more,

and usually far less, egregious than those occuring in other Latin American elections, and even some here in

the U.S. The electoral commissions of Florida and Ohio would do well to adopt SEC methods of conducting an election.

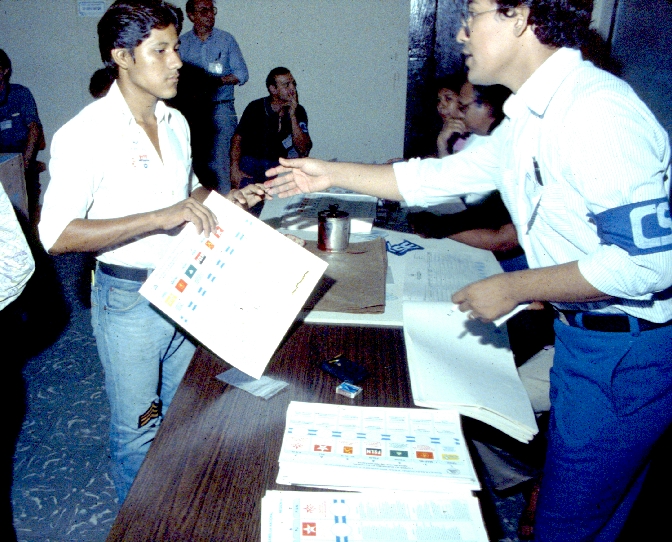

Senor Leonel Arguello, a director of the Supreme Electoral Council, informs our

delegation about the electoral process. The SEC sent delegations to countries around the world to study various

electoral processes and methods, and finally settled on a proportional representation model common to European

countries. The Reagan administration refused to allow Nicaraguan representatives to enter

the U.S. for the purpose of studying our electoral system.

Senor Leonel Arguello, a director of the Supreme Electoral Council, informs our

delegation about the electoral process. The SEC sent delegations to countries around the world to study various

electoral processes and methods, and finally settled on a proportional representation model common to European

countries. The Reagan administration refused to allow Nicaraguan representatives to enter

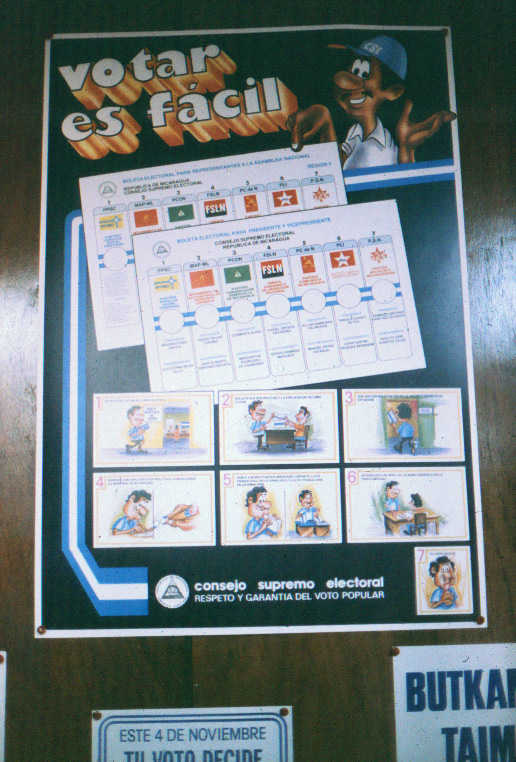

the U.S. for the purpose of studying our electoral system. The Supreme Electoral Council assured Nicaraguans that, in contrast to elections held under the Somoza regime,

this would indeed be a free and fair election.

The Supreme Electoral Council assured Nicaraguans that, in contrast to elections held under the Somoza regime,

this would indeed be a free and fair election. To vote is easy.

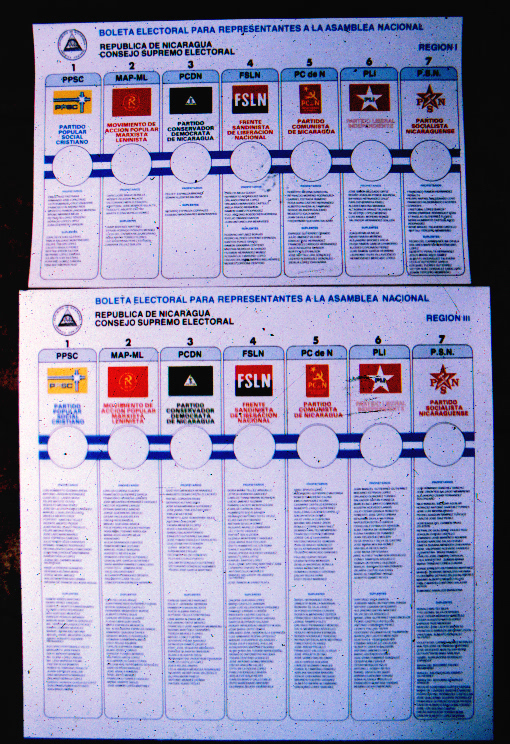

To vote is easy. A closer view of two regional ballots.

A closer view of two regional ballots.

One sector our group observed was in the city of Juigalpa, a lovely town in the low mountains, about

97 kilometers directly east of Managua as the crow flies. Juigalpa is in the conservative, primarily

cattle-raising region of Chontales (electoral Region 5), and was also then home to Nicaragua's most right-wing Catholic bishop,

Pablo Antonio Vega.

One sector our group observed was in the city of Juigalpa, a lovely town in the low mountains, about

97 kilometers directly east of Managua as the crow flies. Juigalpa is in the conservative, primarily

cattle-raising region of Chontales (electoral Region 5), and was also then home to Nicaragua's most right-wing Catholic bishop,

Pablo Antonio Vega. Not far downhill on the same street as the FSLN banner, visible in the distance, this banner says that

Juigalpa will go with the Popular Social Christian Party.

Not far downhill on the same street as the FSLN banner, visible in the distance, this banner says that

Juigalpa will go with the Popular Social Christian Party.

The Communist Party of Nicaragua.

The Communist Party of Nicaragua.

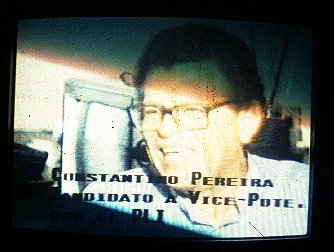

The Liberal Independent Party.

The Liberal Independent Party. On October 21st, the day after a visit from U.S. Ambassador Harry Bergold, and after two months of active campaigning,

PLI candidate Virgilio Godoy withdrew his candidacy for president. Godoy also tried to have the entire

party slate purged from the ballot, but was refused by the SEC because he had withdrawn after the deadline.

On October 21st, the day after a visit from U.S. Ambassador Harry Bergold, and after two months of active campaigning,

PLI candidate Virgilio Godoy withdrew his candidacy for president. Godoy also tried to have the entire

party slate purged from the ballot, but was refused by the SEC because he had withdrawn after the deadline. Each party was given 15 minutes of free TV time each night on the two Sandinista-owned television stations, and

could buy as much radio time as they could afford on Nicaragua's nearly 40 private radio stations.

Each party was given 15 minutes of free TV time each night on the two Sandinista-owned television stations, and

could buy as much radio time as they could afford on Nicaragua's nearly 40 private radio stations. "Vote for the Socialist Party of Nicaragua".

"Vote for the Socialist Party of Nicaragua".

"To vote for the MAP-ML is to vote for the working front. Column 2."

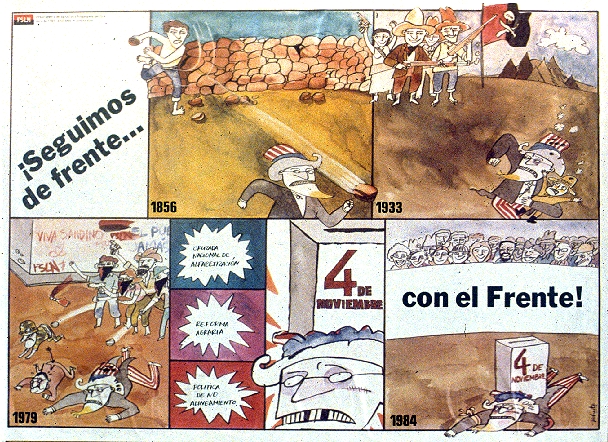

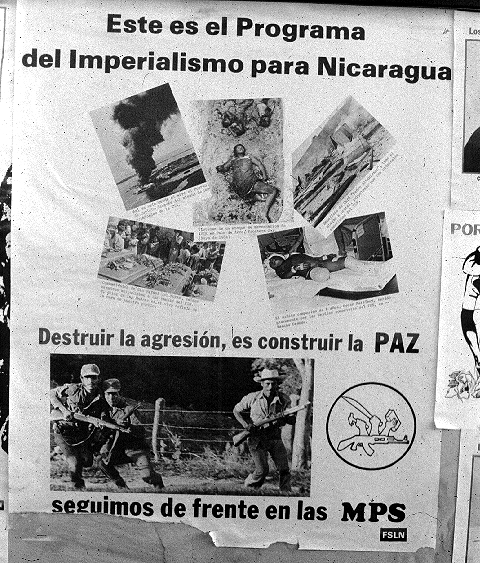

"To vote for the MAP-ML is to vote for the working front. Column 2." "We continue to the front with the Front"

"We continue to the front with the Front" "To Strengthen the Rearguard"

"To Strengthen the Rearguard" "The contras are going to get fucked

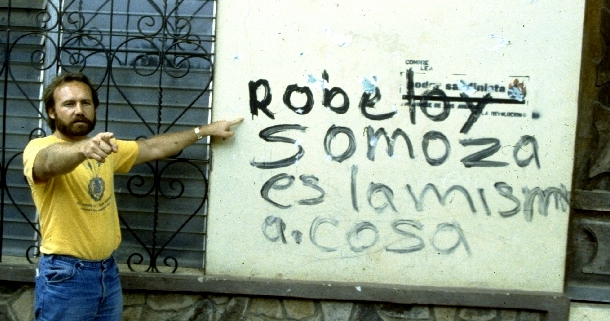

"The contras are going to get fucked A unidentified member of our group draws our attention to a bit of political grafitti:

"Robelo and Somoza are the same thing"

A unidentified member of our group draws our attention to a bit of political grafitti:

"Robelo and Somoza are the same thing" After the vote, everyone to the harvest

After the vote, everyone to the harvest Women were an important part of the Sandinista movement, although, as I recall it, there was never more than

one woman on the 9- or 10-member Sandinista Directorate.

Women were an important part of the Sandinista movement, although, as I recall it, there was never more than

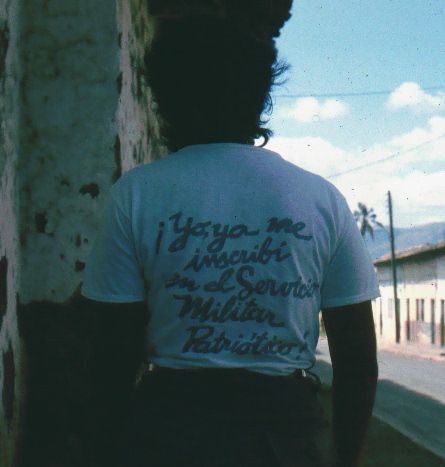

one woman on the 9- or 10-member Sandinista Directorate. "I have already enrolled in the Patriotic Military Service."

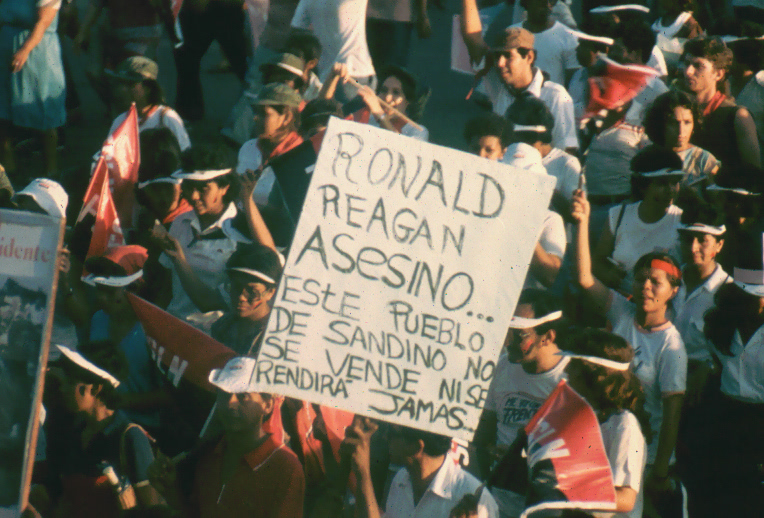

"I have already enrolled in the Patriotic Military Service." Ronald Reagan, Assassin ... The people of Sandino will not sell out or ever surrender.

Ronald Reagan, Assassin ... The people of Sandino will not sell out or ever surrender. Members of the Juigalpa chapter of the Mothers of the Heroes and Martyrs. The plaque commemorates those who died

defending Nicaragua against the contras or against Somoza.

Members of the Juigalpa chapter of the Mothers of the Heroes and Martyrs. The plaque commemorates those who died

defending Nicaragua against the contras or against Somoza.

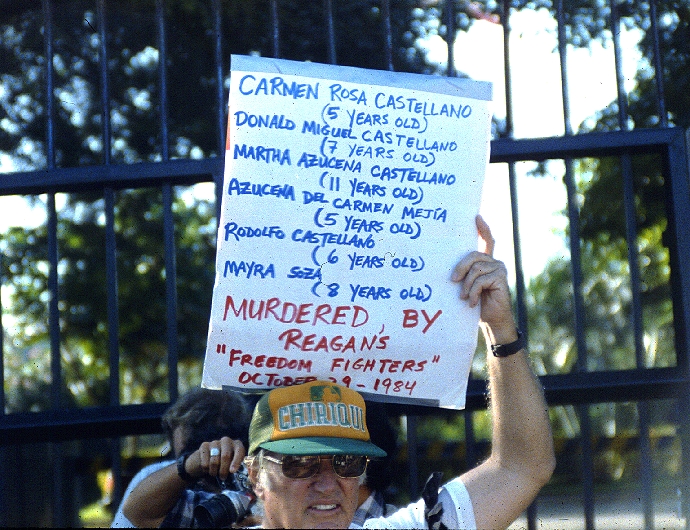

The American religious community living in Managua provided regular opportunities for American visitors

to say "hi" to our employees behind the fence at the American Embassy.

The American religious community living in Managua provided regular opportunities for American visitors

to say "hi" to our employees behind the fence at the American Embassy.  I often wonder if Embassy personnel ever felt the slightest pangs of guilt over Reagan's program.

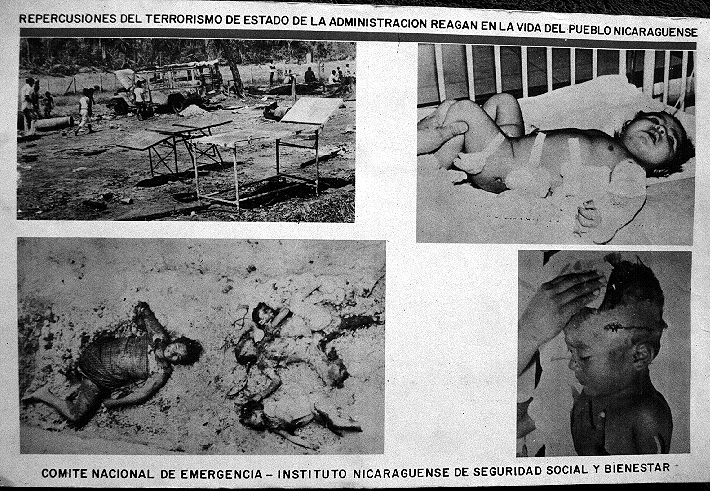

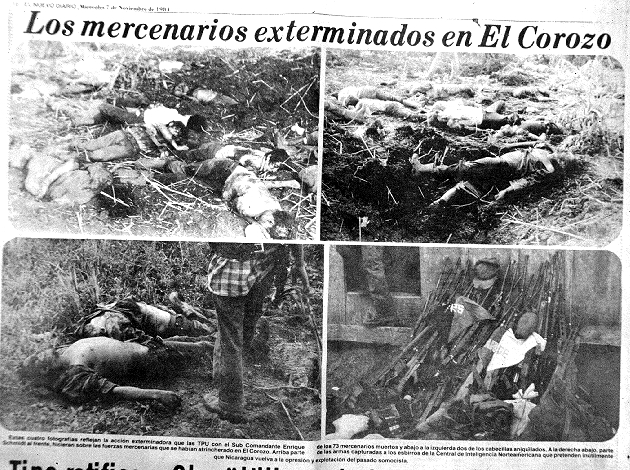

I often wonder if Embassy personnel ever felt the slightest pangs of guilt over Reagan's program. It is likely that these children lived in San Gregorio, and died from a direct contra mortar shell hit

on their house. El Nuevo Diario reported that

Juigalpa's Bishop Antonio Pablo Vega refused to denounce the killings,

"saying instead that 'killing the soul is worse than killing the body and therefore a bomb placed

in the soul is more serious'".

(

It is likely that these children lived in San Gregorio, and died from a direct contra mortar shell hit

on their house. El Nuevo Diario reported that

Juigalpa's Bishop Antonio Pablo Vega refused to denounce the killings,

"saying instead that 'killing the soul is worse than killing the body and therefore a bomb placed

in the soul is more serious'".

(

Can't win 'em all.

Can't win 'em all.

Lined up outside the poll. In our own recent election, our officials should have been as efficient and

professional as Nicaragua's Supreme Electoral Council. On average, each polling station efficiently served

about 400 voters. These folks didn't wait very long to exercise their franchise.

Lined up outside the poll. In our own recent election, our officials should have been as efficient and

professional as Nicaragua's Supreme Electoral Council. On average, each polling station efficiently served

about 400 voters. These folks didn't wait very long to exercise their franchise.

The SCE poll worker, wearing the armband, hands a young voter his ballot. It was decided to allow 16-year-olds

to vote, partly on the argument that if they were old enough to defend their country, as many did as members

of the popular militia, they were old enough to vote.

The SCE poll worker, wearing the armband, hands a young voter his ballot. It was decided to allow 16-year-olds

to vote, partly on the argument that if they were old enough to defend their country, as many did as members

of the popular militia, they were old enough to vote.

Here a poll worker holds the baby of a woman in the voting booth while explaining some aspect of the

voting process to an elderly voter.

Here a poll worker holds the baby of a woman in the voting booth while explaining some aspect of the

voting process to an elderly voter.

I did not ask if I could photograph a voter actually marking his or her bllot. That would have been wrong.

I did not ask if I could photograph a voter actually marking his or her bllot. That would have been wrong.

A voter places his presidential ballot in the proper color-coded box.

A voter places his presidential ballot in the proper color-coded box. Counting the votes. As mentioned above, much of material and other assistance to the Supreme Electoral Council

came from European countries.

Counting the votes. As mentioned above, much of material and other assistance to the Supreme Electoral Council

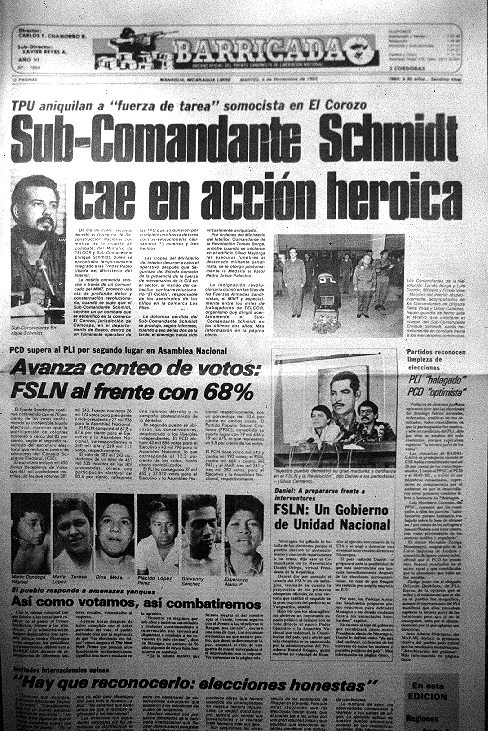

came from European countries. Barricada is the official newpaper of the FSLN. Its preliminary report shows the Sandinistas

ahead with 68% of the vote.

Barricada is the official newpaper of the FSLN. Its preliminary report shows the Sandinistas

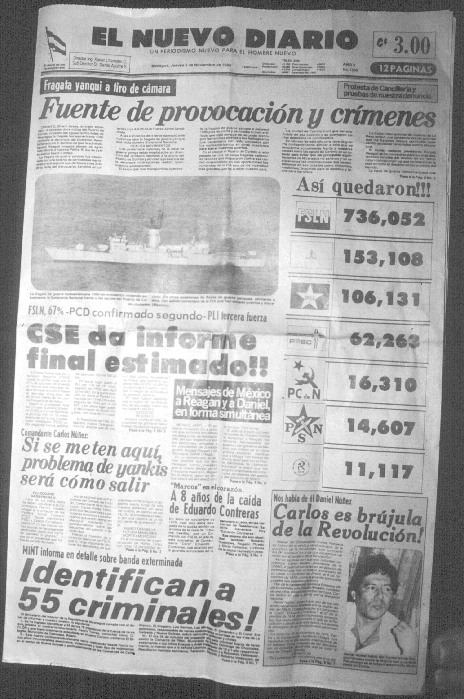

ahead with 68% of the vote. El Nuevo Diario, a new periodical for the new man.

El Nuevo Diario, a new periodical for the new man. La Prensa—owned by Violetta Barrios de Chamorro. Chamorro's husband, Pedro Joaquin

Chamorro, was an implacable foe of Somoza, and was gunned down by masked

thugs in January, 1978. One would think that such an illustrious background of resistance

against tyranny would have inspired Chamorro's widow to enthusiastically embrace the Sandinistas'

"logic of the majority". Alas, it was not to be. La Prensa received serious

funding from the U.S., and produced copy that served U.S. interests very well.

La Prensa—owned by Violetta Barrios de Chamorro. Chamorro's husband, Pedro Joaquin

Chamorro, was an implacable foe of Somoza, and was gunned down by masked

thugs in January, 1978. One would think that such an illustrious background of resistance

against tyranny would have inspired Chamorro's widow to enthusiastically embrace the Sandinistas'

"logic of the majority". Alas, it was not to be. La Prensa received serious

funding from the U.S., and produced copy that served U.S. interests very well.

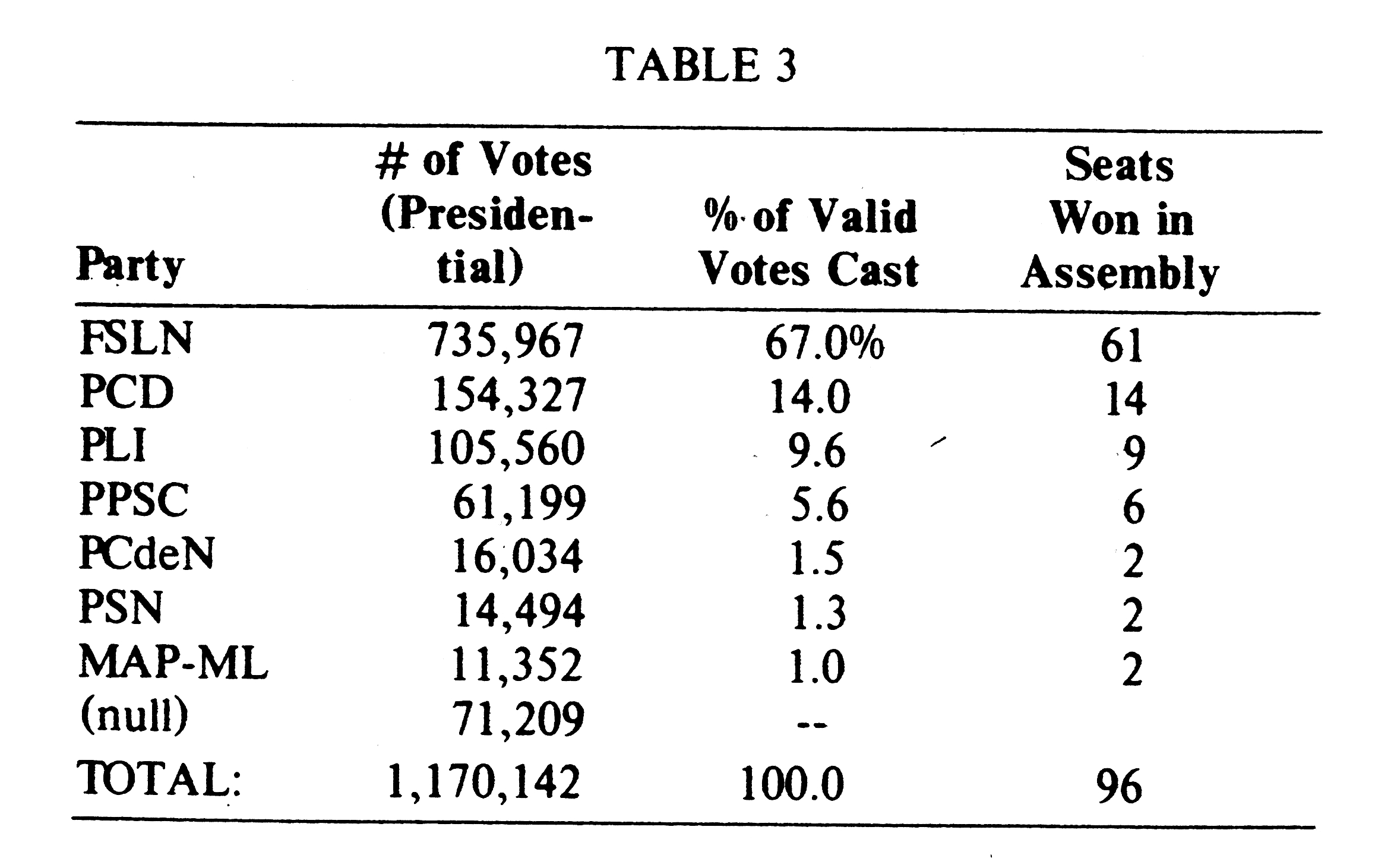

Final result from the report of the Latin American Study Association.

The complete LASA report, in PDF format, is available

Final result from the report of the Latin American Study Association.

The complete LASA report, in PDF format, is available