|

Panama's role as the originator of the Contadora process, which sought a Latin American solution to President

Reagan's war

against the people of Nicaragua, was in large part the heritage of Omar Torrijos Herrera, Panama's president

from 1968 to 1981. Torrijos was a visonary who often mediated quarrels between

various factions in his neighboring Latin American countries. He was also a genuine advocate for Panama's

poor and middle classes, and Panama's elites hated him.

Most of the historical information on Panama I present on this page comes from the book Confessions of an

Economic Hit Man, (CEHM) by John Perkins.

(Berrett-Koehler,

San Francisco, 2004.) CEHM is a must-read for any well-meaning

American in denial about the reasons why the U.S. government—not the people—is so hated

around the world. A few words here to justify this bold statement are in order.

Perkins lived with a guilty conscience almost from the moment he embarked upon his lucrative

career as an economic hit man. He made several abortive efforts to tell his story, and finally decided

to come clean after the events of 9/11. Perkins dedicates CEHM to Omar Torrijos and his fellow

Latin American visionary, Ecuador's President Jaime Roldós.

As Perkins tells it, he was recruited by an official of the National Security Agency (NSA), the most secretive branch

of the U.S. clandestine services. After passing the NSA tests to be a spook, he was seduced by his own

idealism into a stint

with the Peace Corps. His NSA handler approved, adding the mysterious comment that Perkins "might end up

working for a private company instead of the government."

While in Ecuador, he was approached by a vice-president of one of America's most prestigious, and most low

profile, engineering consulting companies: Chas. T. Main (MAIN). Even though Perkins held only a BS

in Business Administration, the MAIN VP asked Perkins to send him

a few write-ups on Ecuador's economic

prospects. Perkins was "quite happy to comply with this request." The MAIN vice-president also confided to

Perkins that he "sometimes acted as a NSA liason."

After completing his term with the Peace Corps, Perkins learned that he had passed the primary

MAIN test: his reports showed that he didn't "mind sticking [his] neck out, even when hard data

isn't available," as the MAIN VP told him later.

At age 26, Perkins was hired

as MAIN's chief economist in charge of producing the economic forecasts that would convince the

World Bank and other

international lenders to lend developing nations "billions of dollars to build hydroelectric dams

and other infrastructure projects." (For all practical purposes, the World Bank is a

wholly-owned subsidiary of the U.S. government.)

No one told Perkins what his job really entailed, so he began educating himself to be an econometrician.

One day, as he studied at the Boston Public Library, Claudine Martin, Special

Consultant to Chas. T. Main, Inc. appeared. Attractive and smart,

Claudine told Perkins that only she was authorized to inform him about the specifics of his job.

Over the next few weeks they would secretly meet in Claudine's

apartment while she told him what was expected of him. He would be an economic hit man, she said.

First, Perkins would "justify huge international loans that would funnel money back to MAIN and other U.S. companies

(such as Bechtel, Halliburton, Stone & Webster, and Brown & Root) through massive engineering and constuction

contracts." Second, he "would work to bankrupt the countries that received those loans (after they had paid

MAIN and the other U.S. contractors, of course) so that they would be forever beholden to their creditors, and

so they would present easy targets when we needed favors, including military bases, UN votes, or access to oil

and other natural resources."

Perkins continues: "The unspoken aspect of every one of these projects was that they were intended

to create large

profits for the contractors, and to make a handful of wealthy and influential families in the

receiving countries

very happy, ... The larger the loan, the better. The fact that the debt burden placed on a country

would deprive its poorest citizens of health, education, and other social services for decades to come was

not taken into consideration."

"We're a rare breed, in a dirty business," Claudine said. "No one can know about your

involvement—not even your wife."

Then Claudine explained to Perkins the genealogy of the EHM. The Vietnam debacle had shown

that a new model for projecting U.S. power

was needed—naked force no longer worked. 32 years before New York Times reporter Stephen Kinzer

would write All The Shah's Men — An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror,

Claudine told Perkins how Theodore Roosevelt's grandson Kermit had orchestrated a CIA coup [code-named

Operation Ajax] against the Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh in 1953. Mossadegh had

nationalized the British-controlled Iranian oil fields in 1951, because of typical British exploitation, arrogance,

and broken promises. He was virtually worshipped by the vast majority of the Iranian people.

But U.S.-sponsored coups can be exposed, and a better solution had been worked out: "U.S. intelligence

agencies—including the NSA—would identify prospective

EHMs, who could then be hired by international corporations. ... their dirty work, if exposed, would be

chalked up to corporate greed rather than to government policy. ... the corporations ... would be insulated

from congressional oversight and public scrutiny, shielded by a growing body of legal initiatives ..."

"So you see," Claudine said, "we are just the next generation in a proud tradition that began when

you were in the first grade."

Perkins "graduated" just before leaving for Indonesia on

his first assignment. Claudine congratulated him with a toast: "You made it. You're now one of us."

Then she warned him: "Never admit to anyone about our meetings. ... Talking about us would make

life dangerous for you."

After returning from Indonesia, Perkins passed his second test. He produced an inflated economic forecast

that MAIN wanted to present to the international lending outfits. He was promoted, and his colleague, a

professional of long experience whose numbers were half those Perkins predicted, was fired.

Perkins sought Claudine, both to tell her the good news of his promotion, and to share some

disturbing experiences in Indonesia. One of those experiences was an ominous prediction from some

Indonesian Muslims to whom Perkins had been introduced. 30 years later, on September 11, 2001, the

prediction was fulfilled.

"It is not farfetched to draw a line from Operation Ajax through

the Shah’s repressive regime and the Islamic Revolution to the

fireballs that engulfed the World Trade Center in New York," wrote

Stephen Kinzer in All the Shah's Men.

The mysterious Claudine had vanished without a trace. More from Perkins below.

|

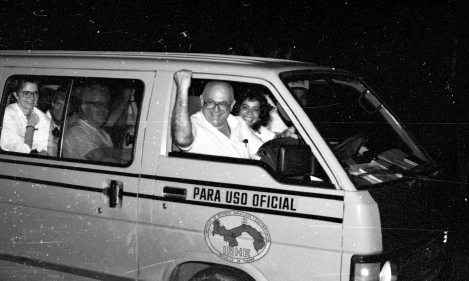

Monday, December 9

Monday, December 9 I'm not sure where exactly we are here. My notes indicate Panama's state-owned power

facility, the Instituto de Recursos Hidraulicos y Electrificación. If so, we are at the same location

where John Perkins, above, met General Omar Torrijos in 1972, and set up the business arrangements for Panama's

"modernization." More on this below.

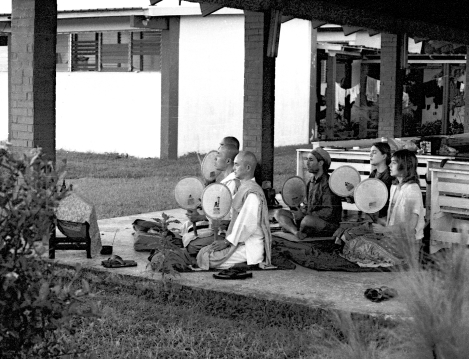

I'm not sure where exactly we are here. My notes indicate Panama's state-owned power

facility, the Instituto de Recursos Hidraulicos y Electrificación. If so, we are at the same location

where John Perkins, above, met General Omar Torrijos in 1972, and set up the business arrangements for Panama's

"modernization." More on this below. Morning prayers.

Morning prayers. Tuesday, December 10, late afternoon.

Tuesday, December 10, late afternoon. It's official. La Marcha Por La Paz En Centroamerica begins on the 37th anniversary of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights.

It's official. La Marcha Por La Paz En Centroamerica begins on the 37th anniversary of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights.

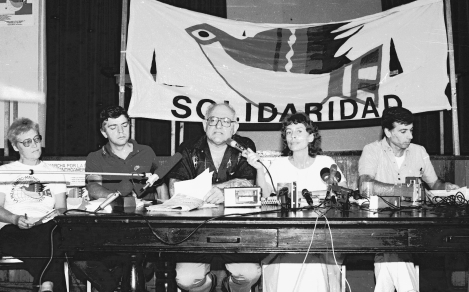

My notes indicate that these Panamanian supporters of the march are leaders of Panama's Social Democrats. Beita

Torillos greeted us warmly: "The march you will do encourages us to continue our struggle for peace."

My notes indicate that these Panamanian supporters of the march are leaders of Panama's Social Democrats. Beita

Torillos greeted us warmly: "The march you will do encourages us to continue our struggle for peace." LA ESTRELLA DE PANAMA

LA ESTRELLA DE PANAMA On The March

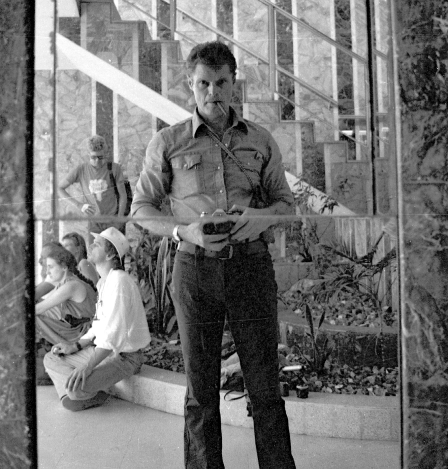

On The March We were joined for the day by Teatro Oveja Negra, the "Black Sheep" Theater troupe.

We were joined for the day by Teatro Oveja Negra, the "Black Sheep" Theater troupe.

As we marched through the well-manicured landscape of Quarry Heights, the site of the U.S. Southern Command,

we made sure that passing motorists noticed us.

As we marched through the well-manicured landscape of Quarry Heights, the site of the U.S. Southern Command,

we made sure that passing motorists noticed us.  Kind of like parts of Beverly Hills.

Kind of like parts of Beverly Hills.

We have arrived at Omar Torrijos Herrera's tomb, where we will pay our respects to the man

who stood up to the United States, as well as being a pretty decent President.

We have arrived at Omar Torrijos Herrera's tomb, where we will pay our respects to the man

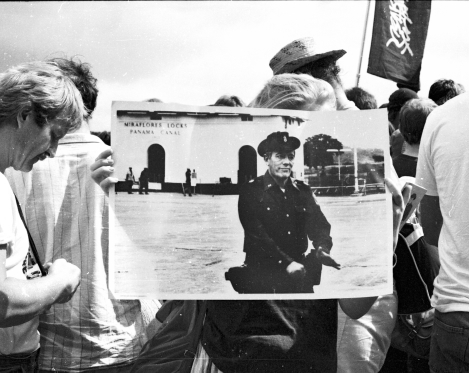

who stood up to the United States, as well as being a pretty decent President. It appears as if Arnie, from Sweden, is preparing to take a picture of this poster showing Omar Torrijos

at the canal's Miraflores Locks, our next destination.

It appears as if Arnie, from Sweden, is preparing to take a picture of this poster showing Omar Torrijos

at the canal's Miraflores Locks, our next destination. Torrijos's tomb. Blase Bonpane's report says that Torrijos's father and sister were also with us, but I don't

have pictures of them. (I now understand why all my friends say that I am left-leaning.)

Torrijos's tomb. Blase Bonpane's report says that Torrijos's father and sister were also with us, but I don't

have pictures of them. (I now understand why all my friends say that I am left-leaning.) We laid a wreath on Torrijos's crypt. Dianne from Cananda looks on.

We laid a wreath on Torrijos's crypt. Dianne from Cananda looks on. The Miraflores Locks

The Miraflores Locks One of the two Love Boats.

One of the two Love Boats.

I'm pretty sure that the large banners were made by the Norwegian contingent.

I'm pretty sure that the large banners were made by the Norwegian contingent.

Canada and Central America for Friendship, Peace, and Liberty. Pretty subversive.

Canada and Central America for Friendship, Peace, and Liberty. Pretty subversive.  A canal for peace, not for aggression against the people.

A canal for peace, not for aggression against the people. Scotland for Peace

Scotland for Peace  Thursday, December 12.

Thursday, December 12. Canadians Susie, Jerry in the middle, and a compatriot display the Canadian banner in front of the

Howard AFB gate.

Canadians Susie, Jerry in the middle, and a compatriot display the Canadian banner in front of the

Howard AFB gate.  The Panamanian Defense Force is ready for us.

The Panamanian Defense Force is ready for us. The Vikings. The woman in the green dress to the right of the front line is a "general."

The Vikings. The woman in the green dress to the right of the front line is a "general."

Some yanks.

Some yanks.

More yanks. Bruce, a quadriplegic from Berkeley, California, emerged as one of the U.S. contingent's wisest

counselors.

More yanks. Bruce, a quadriplegic from Berkeley, California, emerged as one of the U.S. contingent's wisest

counselors.

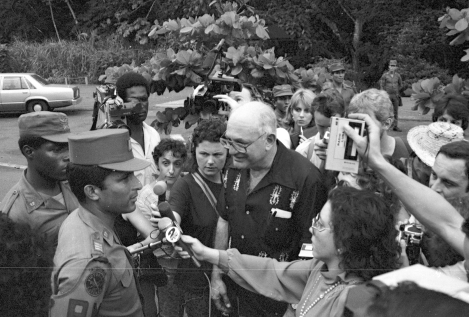

Australia's Penny O'Donnell (in the dark shirt) holds the mike as Blase Bonpane tries to convince the Panamanian officer in charge

that la marcha poses no threat to the Howard Base. No luck.

Australia's Penny O'Donnell (in the dark shirt) holds the mike as Blase Bonpane tries to convince the Panamanian officer in charge

that la marcha poses no threat to the Howard Base. No luck.  The Buddhist monks fared no better.

The Buddhist monks fared no better.  Even Ollie was refused entry. How could anyone see this elderly gentleman as a threat? I hope that

the Spanish marchista looking askance at the officer is mentally rehearsing some choice phrases—en

Español—not for the officer, who had no choice, but for the U.S. government.

Even Ollie was refused entry. How could anyone see this elderly gentleman as a threat? I hope that

the Spanish marchista looking askance at the officer is mentally rehearsing some choice phrases—en

Español—not for the officer, who had no choice, but for the U.S. government.

Friday, December 13.

Friday, December 13. After the barbecue, we celebrate our hosts' generosity and solidarity until dark, "to the astonishment of the

farmers," as Mel Fiske put it in his December 30 report on the march. California farm worker Francisco

stands left of the guitarist, who looks to me to be one of

our local supporters. A couple of Spanish marchistas whose names I don't have are close by.

Barbara

looks directly at the camera above the mike on the left. More on Barbara later.

After the barbecue, we celebrate our hosts' generosity and solidarity until dark, "to the astonishment of the

farmers," as Mel Fiske put it in his December 30 report on the march. California farm worker Francisco

stands left of the guitarist, who looks to me to be one of

our local supporters. A couple of Spanish marchistas whose names I don't have are close by.

Barbara

looks directly at the camera above the mike on the left. More on Barbara later. Saturday, December 14.

Saturday, December 14. Steve Zrucky and Paula collect water flowing over the concrete dock surface. Here, Paula fills a cut-off

1.75-liter plastic soda bottle serving as a bowl—for washing, I assume. (These bottles were everywhere,

and were ideal for storing water.)

Steve Zrucky and Paula collect water flowing over the concrete dock surface. Here, Paula fills a cut-off

1.75-liter plastic soda bottle serving as a bowl—for washing, I assume. (These bottles were everywhere,

and were ideal for storing water.) When we were not marching, banners doubled as privacy curtains for our portable outhouses.

When we were not marching, banners doubled as privacy curtains for our portable outhouses.

For the really curious: your basic heavy cardboard, plastic lined, deluxe model porta-potty, with lid.

The cardboard box was reused, of course, and for obvious

reasons we treated them very gently.

For the really curious: your basic heavy cardboard, plastic lined, deluxe model porta-potty, with lid.

The cardboard box was reused, of course, and for obvious

reasons we treated them very gently. Saturday, December 14, later.

Saturday, December 14, later. We sleep in the buses. Here, Mel Fiske nurtures the bug that will ultimately send him home.

We sleep in the buses. Here, Mel Fiske nurtures the bug that will ultimately send him home.

And we sleep on the street. Later, the Canadians rejoin us. "People slept better," noted Mel.

And we sleep on the street. Later, the Canadians rejoin us. "People slept better," noted Mel.

Sunday morning, December 15.

Sunday morning, December 15. Peter Holding seems undecided on which bus to board.

Peter Holding seems undecided on which bus to board.