|

La Marcha was purposefully scheduled to be in Guatemala for the inauguration of the

new president, Vinicio Cerezo Arevalo. Guatemala was host to the longest-running

revolutionary movement in the hemisphere. Begun in 1961, it was a response to

a succession of unspeakably brutal governments, all of which enjoyed Washington's

unstinting support and friendship. (For a fine account of the CIA-orchestrated overthrow of the

progressive, and democratically elected Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz in 1954, and the

installation of the first of this series of brutal regimes, see Bitter Fruit: The Story

of the American Coup in Guatemala, by Stephen C. Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer.)

As I recall it, Cerezo—a member of Guatemala's upper class—had nevethelss been an opponent of the

repression, and had been arrested and tortured by the military. In a radical departure from all

previous U.S. Presidents, Jimmy Carter actually said out loud that human rights were important, and thereby

helped make U.S. support for Guatemala's hyper-brutal repression something of a liability. This in turn helped to

make Cerezo's election to the Guatemalan presidency possible.

Thus, the peace and justice community around the world, along with millions of Guatemala's poor, hoped that Cerezo

would be able to at least mitigate the horrendous human rights violations committed by the Guatemalan military against

Guatemala's Indian community. La Marcha wanted to show Cerezo that he had international support for any such

efforts he might make. ¡Que lastima! After all was said and done, Cerezo turned out to be just as corrupt as

his predecessors.

My notes show that as of the morning of January 10, a charter flight into Guatemala City seemed possible,

but it is likely that opposition from the Guatemalan military put an end to that idea. They would not

benefit from a well-publicized, international peace and justice group coming in overtly to draw attention

the worst human rights record in the hemisphere.

Thus, we proceeded with the plan which we had prepared: we would fly in as small groups of "tourists,"

trying not to draw attention to ourselves. We would be met at the airport by marchistas who had arrived

earlier, and receive from them advice and directions to the local pensions which would be our home for

the next 4 days. Tickets had already been purchased for most of the group—I seem to recall helping

in that process myself—and I am not aware that any problems in entering Guatemala were encountered

by any of the marchers. (More on this below.)

Whether by accident or by design, Theresa from Canada; Anna from Scotland; Jodi and Eric from

Minnesota and I formed a little band of "tourists" for our departure, and we pretty much hung

out together during our stay in Guatemala. We arrived at the airport

in Managua at 6:30 p.m., and were pleased to learn that the Sandinistas waived the standard $10 tax.

Money was running short for some of us, and the gift was greatly appreciated. The plane left the

runway at 7:20. We touched down in San Salvador, El Salvador at 8:02, and took off from there at

8:32 without disembarking. We landed at the Guatemala City International Airport at 8:55 p.m.

My sketchy notes show that while we were on the plane, Theresa and Jodi were questioned by a man sitting

near them. Where were they from?

"Canada," they answered. They probably added that they were here as tourists, although my

notes don't say specifically that they did.

"Do you see those people over there," he asked, pointing at several of us marchistas. "They're all

Cubans and Russians."

"Really," asked our "tourists."

"Yes," he affirmed.

"All of them?"

"Yes," he insisted. "I'm from Costa Rica," he said. "Costa Rica is different. It's

99% like the U.S. We have no military, and we have lots of freedom."

This man revealed the same degree of political sophistication as his

Costa Rica Libre compatriots.

We found a pension—the MEZA, and a great restaurant—The Picadilly, located as I recall

on Guatemala City's main drag, 6th Avenue.

We had a very good pizza, and we paid in dollars instead of

Guatemalan quetzales. After dinner we walked around the neighborhood playing dumb tourists.

It was now after 10:30, and it was chilly outside. Our first sight out of the

restaurant was of a small figure huddled in a shop doorway. Across the street two

women and three children huddled in another doorway.

The next morning, the 11th, I went to the tourist center to get maps,

changed money, bought toilet paper and toothpaste. While walking around town—whether alone

or with my little band my notes don't indicate—I met Steven, Stan, and Daniel, and

received an update on Brigido Sanchez's situation in El Salvador from Daniel. (See the Salvador page.)

January 12th

The daily paper Prensa Libre carried a diatribe from a right-wing Guatemalan political type

condemning Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, who had been invited to attend Cerezo's inauguration.

Ortega was accused of

being responsible for the deaths of Guatemalan soldiers and officials, but we marchistas had

never heard of any direct hostilities between the two countries. Perhaps the politician was

referring to Guatemalan soldiers and officials who were covert CIA operatives, and who

perhaps had been caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Tom, from Minnesota, related that he had attended a talk by a Guatemalan woman at

the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua (UNAN). She spoke about Guatemala's spy network, and

about how dangerous

it was to talk openly against the government. She also told him some horror stories, which he

either did not relate, or which I did not record. I recall being approached by a very

friendly Guatemalan who asked a lot of questions and offered me a private tour of the city.

I respectfully declined.

That evening, Tom and I waited at the airport for an American from Miami who was scheduled to join us.

In fact, I wished that I had been there the night before, to greet him. As he told the story, he was walking toward the

baggage check area when he heard a loud voice behind him: "Tom ..., I'm from the CIA, and

we're not going to let you into Guatemala." Tom froze, then turned to see the speaker. It was one

of the Americans he had seen January 6th, at the meeting with U.S. embassy official Sweeney in

Managua. This fellow had followed us to Guatemala, and apparently had been instructed to

have a little fun with us.

It worked. Tom had calmed down by the time he told his story, but he said he broke out

in the proverbial cold sweat during the encounter. My notes don't say what Tom's response to

his tormentor was, but I recall expressing quite vividly my own regret that I had not been the one

our spook employee had decided to confront. Perhaps

foolishly, at the time I would have given my eye teeth to have

been able to confront this CIA compatriot with my own opinions on his choice of

livelihood, and perhaps his lineage as well. If I had attended the meeting at the

embassy, perhaps I might have been the lucky one. (On the other hand, I'm not totally dumb.

Had it actually

been me, given the repercussions that I knew could affect the march as a whole,

I might well have been quite circumspect in my response.)

January 13:

I called home. Dinner at Los Cebollinos, which had become my favorite restaurant. I

have no other notes for the day.

January 14, Tuesday:

Cerezo will be inagurated today at the National Theater at 9:15 a.m. This evening he will address

Guatemala and the world from the National Palace. It promises to be a memorable day.

In response to the repression, Guatemala's Indian community formed the El Grupo De Apoyo Mutuo,

The Group of Mutual Support [for the reappearance alive of the disappeared, as I once

heard the full title expressed]. GAM, with its contacts in the global human rights community,

was a painful thorn in the side of the Guatemalan government and the oligarchy. GAM would be

there for Cerezo's inauguration and for his later inaugural address. La Marcha would be

there too. We did not plan to hide our light under a bushel.

|

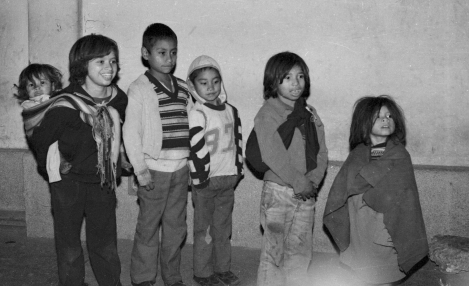

It's near midnight, and this little band is only one of many we saw on the

streets of downtown Guatemala City.

It's near midnight, and this little band is only one of many we saw on the

streets of downtown Guatemala City.